The via Francigena is one side of the great triangle of middle age pilgrimage routes linking northern Europe with Santiago de Compostela and Rome and largely follows the Roman roads that facilitated trade and military deployment after the conquest of Britain initiated by Julius Caesar beginning in 55 BC.

Today the route is conventionally travelled from Canterbury Cathedral to St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, although the first written record of the route was produced by a clerk to Archbishop Sigeric the Serious on his return from Rome to Canterbury.

![]() Modern signposted route

Modern signposted route![]() Sigeric’s probable route

Sigeric’s probable route

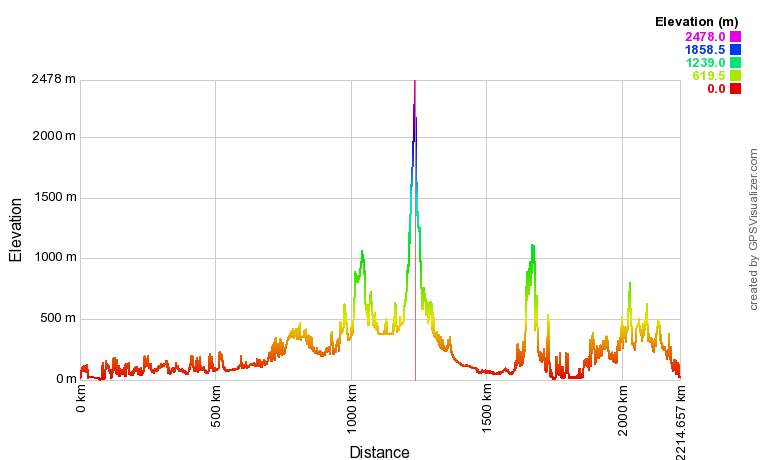

Total distance following the signposted route: 2262km

Maximum Altitude: 2469m – Col Grand Saint Bernard

The via Francigena is not a single road, but a collection of several possible routes that changed over the centuries as trade and the pilgrimage culture developed and waned. Depending on the time of year, political situation, and relative popularity of the shrines of saints along the route, travellers may have used any of three or four crossings over the Alps and the Apennines.

First documented as th e Lombard Way and later the Iter Francorum, the via Francigena was only mentioned as such in the Actum Clusi, a parchment produced in 876 in the Abbey of San Salvatore al Monte Amiata (Tuscany).

e Lombard Way and later the Iter Francorum, the via Francigena was only mentioned as such in the Actum Clusi, a parchment produced in 876 in the Abbey of San Salvatore al Monte Amiata (Tuscany).

It seems that it was first in England in the 7th century that it became accepted that no archbishop could exercise his authority over his jurisdiction until he had received a pallium from Rome, a practice that was soon widely accepted in the western church. At the end of the 10th century, Sigeric the Serious, Archbishop of Canterbury, used the via Francigena to travel to Rome (or more certainly to return from Rome) where he received his pallium from the Pope. He recorded his return journey, and the places where he stopped, in a document which is now held in the British Library, but nothing in it suggests that the route was new. His itinerary lists the seventy-nine submansiones, which define the via Francigena as we know it today.

Archbishop Sigeric’s Pilgrimage to Rome in 990 – Veronica Ortenberg

St Thierry, known as William of St Thierry, used the roads towards Rome on several occasions at the end of the 11th century. Other itineraries include those of the Icelandic traveller Nikolás Bergsson in 1154 and Philip Augustus of France, who entered Italy via Moncenisio in 1191. Subsequent accounts also cite the pass over Montgenévre and through the Susa Valley as a route used by both pilgrims travelling to Rome (along what is now recognised as a branch of the via Francigena) and armies invading Italy. In the 12th century the increase in commercial relations between Italy and the Germanic areas led to a renewed use of the passes in the central and eastern Alps, like the St Gotthard and Brenner passes. Nevertheless, the via Francigena route described by Sigeric was still in frequent use, as evidenced in the journey of Barthelemy Bonis, a merchant of Montauban,who took part in the Jubilee of 1350, having survived the plague of 1348. Other documents also recordCharles VIII’s journey along the Via Francigena in 1494, as part of his armed descent on Naples.

The via Francigena facilitated all forms of exchange between communities, one of the clearest examples being in art and culture. How else can we explain the presence of an 8th century Scotic-Irish relic in the monastery of San Salvatore L’Amiata, or the vestment made from traditional Persiansamite (a luxurious and heavy silk fabric often including gold or silver thread) dating back to the Carolingian age? Or the Codex Amiatinus, an 8th century English Bible and the Vercelli Book, left there by a Scotic pilgrim in the 6th century.

Similarly, architects and builders were clearly open to the external influences brought in by the via Francigena. Tightly woven exchanges can be seen between the Lombard Romanesque style, or more generically that of the Po region and France. A prime example of this can be found in the work of Nicolao, a sculptor who between 1120 and 1140 was working on the abbey of San Michele della Chiusa in Piacenza obviously inspired by the Wiligelmic tradition, but also by the art of the Aquitaine. In Tuscany, where French architectural styles are evident in buildings both along and near the via Francigena, the abbey church of Sant’Antimo is the only one to have a basilica plan, complete with the aisle and side chapels typical of the great pilgrimage churches in France and Santiago de Compostela.

This 1988 paper by Paul von Caucci Saucken provides more information on the relationship between the via Francigena and routes to Santiago

In line with the renaissance of the pilgrim experience, precipitated by the St James Way, the via Francigena is also being rediscovered. Since receivi ng its title of European Cultural Route in 1994, significant funds have been dedicated first by the Italian Prime Minister, Romano Prodi, and subsequently by the Italian Ministry of Culture for the signing of an official route in Italy.

ng its title of European Cultural Route in 1994, significant funds have been dedicated first by the Italian Prime Minister, Romano Prodi, and subsequently by the Italian Ministry of Culture for the signing of an official route in Italy.

In 2007, the 0km foundation stone was laid in the forecourt of Canterbury Cathedral and since then pilgrim numbers have increased year on year.

In 2007, the 0km foundation stone was laid in the forecourt of Canterbury Cathedral and since then pilgrim numbers have increased year on year.

In spite of these ongoing changes – better and more frequent signs, cheaper and more numerous hostels – which certainly make the route an easier one to follow, the Via Francigena is not the St James Way, and perhaps not everyone wants it to be. For some, the Camino experience is the perfect introduction, offering support, companionship and a relatively safe (apart from the busy roads) environment to walk in. The via Francigena can be a harder and perhaps more authentic alternative where pilgrims must expect to rely on their own resources, but as a consequence will also benefit a great deal more from their interactions with local people and a greater sense of achievement.

Similarly, architectural and cultural highlights are well identified and frequented along the St James Way, but this does not mean that there are any less along the Via Francigena. Far from it, pilgrims just have to be prepared to spend a little more time in finding them.

In Great Britain the route follows the North Downs Way from Canterbury to Dover. You will find a number of via Francigena signs on the route.

In France a “grand randonée” route(GR145) is progressively being developed by melding existing GR pathways that roughly parallel the ancient route.

In Switzerland there is a well signposted route “Swissmobility walking route 70”. However, this is based on a misinterpretation of the route of Sigeric and makes large diversions from the probable historic route.

In Italy there has been substantial investment in signposting throughout the route with efforts to find safe pathways as close as possible to the historic route and with an ongoing program of improvement to infrastructure to offer minimum distance and greatest authenticity subject to the demands of safety.

The modern via Francigena route in the map above is the result of our most recent surveys and generally follows the signposted routes. The Lightfoot Guides add greater detail and propose a large number of alternatives to improve authenticity and reduce overall distance.

As you will see the route follows much more closely the route of Sigeric and where practical passes close to each submansion.

Click here to download the GPS trackThe map below shows the extension of the bike route from Rome to Brindisi – perhaps one of the many routes used by pilgrim’s continuing their journey towards Jerusalem and today known as the via Francigena della Sud. The route was kindly provided by Massimo Mazzone.

Click here to download the GPS track